Reprinted from IEEE Computer, Sepetember 1989, pp. 11-29

Content sourced from GuideBookGallery.org

The Xerox Star: A Retrospective

Jeff Johnson and Teresa L. Roberts, US West Advanced Technologies

William Verplank, IDTwo

David C. Smith, Cognition, Inc.

Charles H. Irby and Marian Beard, Metaphor Computer Systems

Kevin Mackey, Xerox

The Xerox Star has significantly affected the computer industry. In this retrospective, several of Star’s designers describe its important features, antecedents, design and development, evolution, and some lessons learned.

Introduction

Xerox introduced the 8010 “Star” Information System in April of 1981. That introduction was an important event in the history of personal computing because it changed notions of how interactive systems should be designed. Several of Star’s designers, some of us responsible for the original design and others for recent improvements, describe in this article where Star came from, what is distinctive about it, and how the original design has changed. In doing so, we hope to correct some misconceptions about Star that we have seen in the trade press and to relate some of what we have learned from designing it.

For brevity, we use the name “Star” here to refer to both Star and its successor, ViewPoint. “ViewPoint” refers exclusively to the current product.

What Star is

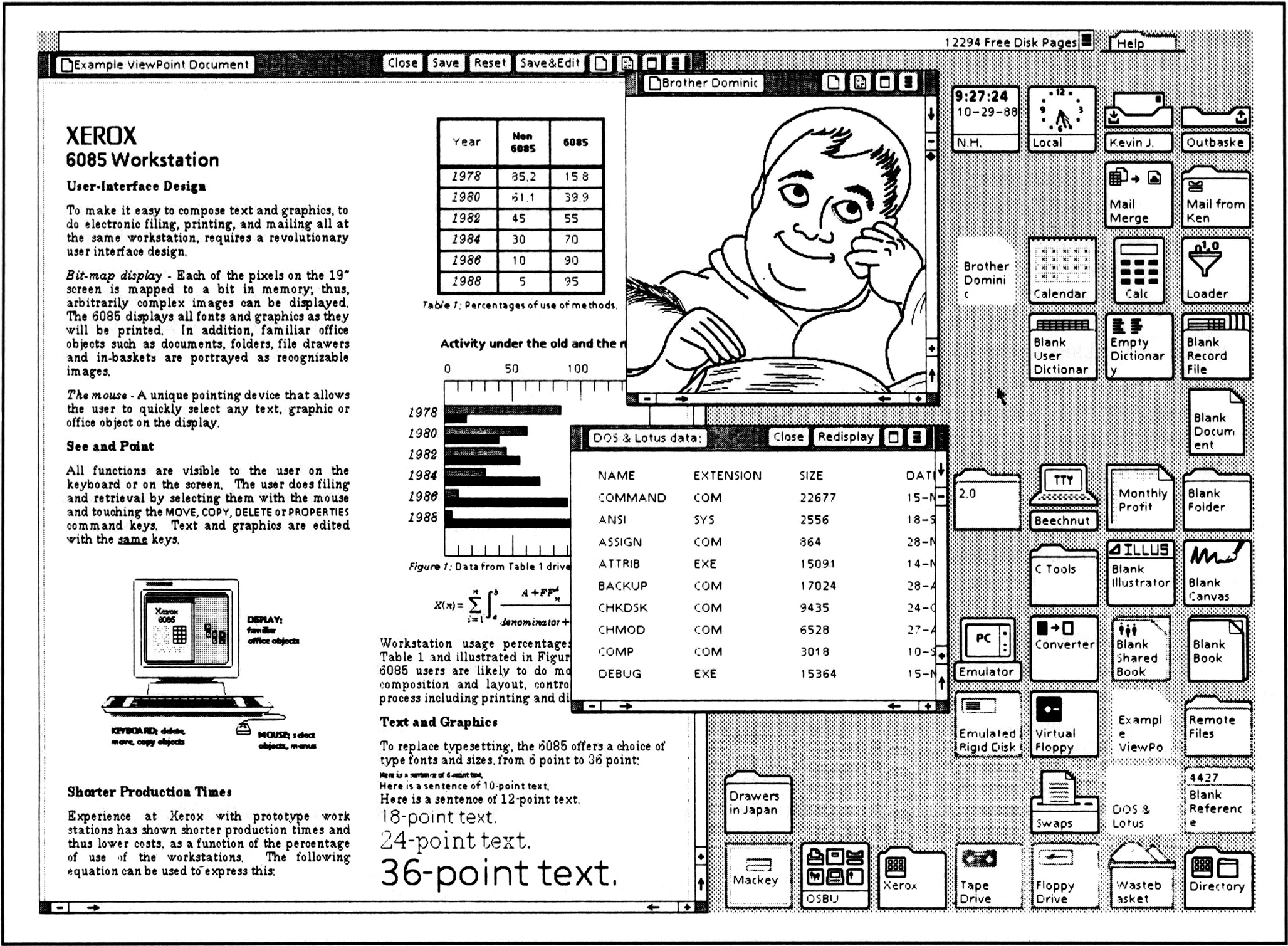

Star was designed as an office automation system. The idea was that professionals in a business or organization would have workstations on their desks and would use them to produce, retrieve, distribute, and organize documentation, presentations, memos, and reports. All of the workstations in an organization would be connected via Ethernet and would share access to file servers, printers, etc.

Star’s designers assumed that the target users were interested in getting their work done and not at all interested in computers. Therefore, an important design goal was to make the “computer” as invisible to users as possible. The applications included in the system were those that office professionals would supposedly need: documents, business graphics, tables, personal databases, and electronic mail. The set was fixed, always loaded, and automatically associated with data files, eliminating the need to obtain, install, and start the right application for a given task or data file. Users could focus on their work, oblivious to concepts like software, operating systems, applications, and programs.

Another important assumption was that Star’s users would be casual, occasional users rather than people who spent most of their time at the machine. This assumption led to the goal of having Star be easy to learn and remember.

When Star was introduced in 1981, its bitmapped screen, windows, mouse-driven interface, and icons were readily apparent features that clearly distinguished it from other computers. Soon, however, others adopted these features. Today, windows, mice, and icons are more common. However, Star’s clean, consistent user interface has much more to do with its details than with its gross features. We list here the features that we think make Star what it is, categorized according to their level in the system architecture: machine and network, window and file manager, user interface, and document editor.

Machine and Network Level

Important aspects of Star can be found in the lowest levels of its architecture: the machine and the network of which it is a part.

Distributed, personal computing. Though currently available in a standalone configuration, Star was designed primarily to operate in a distributed computing environment. This approach combines the advantages and avoids the disadvantages of the two other primary approaches to interactive computing: time-shared systems and stand-alone personal computers.

Time-shared systems, dominant through the sixties and seventies, allow sharing of expensive resources like printers and large data stores among many users and help assure the consistency of data that many must use. Timesharing has the disadvantages that all users depend upon the continued functioning of the central computer and that system response degrades as the number of users increases.

Personal computers, which have replaced timesharing as the primary mode of interactive computing, have the advantage, as one Xerox researcher put it, “of not being faster at night.” Also, a collection of personal computers is more reliable than are terminals connected to a centralized computer: system problems are less apt to cause a total stoppage of work. The disadvantages of PCs, of course, are the converse of the advantages of timesharing. Companies that use stand-alone PCs usually see a proliferation of printers, inconsistent databases, and nonexchangeable data.

The solution, pioneered by researchers at Xerox (see “History of Star development” below) and embodied in Star, is to connect personal workstations with a local area network and to attach shared resources (file servers, database servers, printers) to that same network.

Mouse. An interactive computer system must provide a way for users to indicate which operations they want and what data they want those operations to be performed on. Users of early interactive systems specified operations and operands via commands and data descriptors (such as text line numbers). As video display terminals became common, it became clear that it was often better for users to specify operands – and sometimes operations – by pointing to them on the screen. It also became clear that graphic applications should not be controlled solely with a keyboard. In the sixties and seventies, people invented many different pointing devices: the light pen, the trackball, the joystick, cursor keys, the digitizing tablet, the touch screen, and the mouse.

Like other pointing devices, the mouse allows easy selection of objects and triggering of sensitive areas on the screen. The mouse differs from touch screens, light pens, and digitizing pads in that it is a relative pointing device: the movement of the pointer on the screen depends upon mouse movement rather than position. Unlike light pens, joysticks, and digitizing pads, the mouse (and the corresponding pointer on the screen) stays put when the user lets go of it.

To achieve satisfactory mouse-tracking performance, Star handles the mouse at a very low level. In some workstations, the window system handles mouse tracking, with the result that the mouse pointer often jerks around the screen and may even freeze for seconds at a time, depending upon what else the system is doing. The mouse is a hand-eye coordination device, so if the pointer lags, users just keep moving the mouse. When the system catches up, the mouse moves beyond the user’s target. We at Xerox considered this unacceptable.

Star uses a two-button mouse, in contrast with the one-button mouse used by Apple and the three-button mouse used by most other vendors. Though predecessors of Star developed at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (see “History of Star development” below) used a three-button mouse, Star’s designers wanted to reduce the number of buttons to alleviate confusion over which button did what. Why stop at two buttons instead of reducing the number to one, as Apple did? Because studies of users editing text and other material showed that a one-button mouse eliminated button-confusion errors only at the cost of increasing selection errors to unacceptable levels.

Bitmapped display. Until recently, most video display terminals were character-mapped. Such displays enable vast savings in display memory, which, when memory was expensive, made terminals more affordable.

In the seventies, researchers at Xerox PARC decided that memory would get cheaper eventually and that a bitmapped screen was worth the cost anyway. They thus developed the Alto, which had a screen 8.5 inches wide and 10.5 inches tall and an instruction set specially designed for manipulating display memory.

Like the Alto, Star’s display has a resolution of 72 pixels per inch. The number 72 was chosen for two reasons. First, there are 72 printer’s points per inch, so 72 pixels per inch allows for a smooth interface with the world of typesetting and typography. Second, 72 pixels per inch is a high enough resolution for on-screen legibility of a wide range of graphics and character sizes (down to about eight points – see Figure 1), but not so high as to cause an onerous memory burden, which a screen that matched the 300 dots-per-inch printer resolution would have. Unlike many PC graphic displays, the pixel size and density are the same horizontally and vertically, which simplifies the display software and improves image quality.

Window and File Manager Level

Just above Star’s operating system (not discussed here) are facilities upon which its distinctive user interface rests.

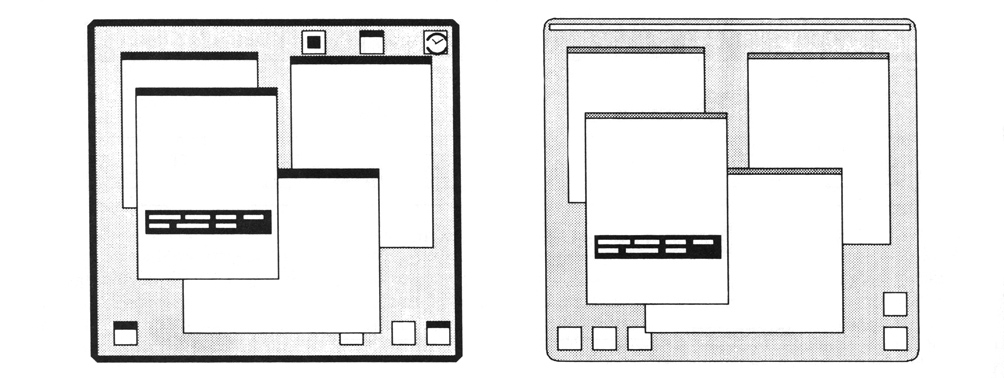

Windows Systems now commonly allow several programs to display information simultaneously in separate areas of the screen, rather than each taking up the entire display. Star was the first commercial system to provide this capability.

Some windowing systems allow windows to overlap each other. Other systems don’t; the system adjusts the size and position of windows as they are opened and closed. Star’s windowing system could overlap windows and often did (for example, property sheets appeared in windows overlapping application windows). However, early testing revealed that users spent a lot of time adjusting windows, usually so they did not overlap. Because of this, and because Star’s 17-inch screen reduced the need for overlapping windows, the designers decided to constrain application windows to not overlap. However, some situations benefit from overlapping application windows. This, added to a subsequent reduction in the standard screen size to 15 inches (with a 19-inch screen optional), resulted in optional constraints for ViewPoint, Star’s successor, with the default setting allowing application windows to overlap one another.

Integrated applications. “Integrated” has become a buzzword used to describe many things. Here, it means that text, graphics, tables, and mathematical formulas are all edited inside documents. In many other systems, different types of content are edited in separate application windows and then cut and pasted together. For example, a MacDraw drawing put into a Microsoft Word or Aldus Pagemaker document can no longer be edited; rather, the original must be re-edited with MacDraw and then substituted for the old drawing in the document.

Not even Star is fully integrated in the sense used here. For example, though the original structured graphics editor, the new one (see “History of Star development” below), and the table and formula editors all operate inside text files, spreadsheets and freehand drawings are currently edited in separate application windows and transferred into documents, where they are no longer fully editable.

User-Interface Level

Star’s user interface is its most outstanding feature. In this section we discuss important aspects of the interface in detail.

Desktop metaphor. Star, unlike all conventional systems and many window- and mouse-based ones, uses an analogy with real offices to make the system easy to learn. This analogy is called “the Desktop metaphor.” To quote from an early article about Star:

Every user’s initial view of Star is the Desktop, which resembles the top of an office desk, together with surrounding furniture and equipment. It represents a working environment, where current projects and accessible resources reside. On the screen are displayed pictures of familiar office objects, such as documents, folders, file drawers, in-baskets, and out-baskets. These objects are displayed as small pictures, or icons.

The Desktop is the principal Star technique for realizing the physical office metaphor. The icons on it are visible, concrete embodiments of the corresponding physical objects. Star users are encouraged to think of the objects on the Desktop in physical terms. You can move the icons around to arrange your Desktop as you wish. (Messy Desktops are certainly possible, just as in real life.) You can leave documents on your Desktop indefinitely, just as on a real desk, or you can file them away.1

Having windows and a mouse does not make a system an embodiment of the Desktop metaphor. In a Desktop metaphor system, users deal mainly with data files, oblivious to the existence of programs. They do not “invoke a text editor,” they “open a document.” The system knows the type of each file and notifies the relevant application program when one is opened.

Most systems, including windowed ones, use a Tools metaphor, in which users deal mainly with applications as tools. Users start one or more application programs (such as a word processor or spreadsheet), then specify one or more data files to edit with each. Such systems do not explicitly associate applications with data files. Users bear the burden of doing that – and of remembering not to try to edit a spreadsheet file with the text editor or vice versa. User convention distinguishes different kinds of files, usually with filename extensions (such as memo.txt). Star relieves users of the need to keep track of which data file goes with which application.

SunView is an example of a window system based upon the Tools metaphor rather than the Desktop metaphor. Its users see a collection of application program windows, each used to edit certain files. Smalltalk-80, Cedar, and various Lisp environments also use the Tools metaphor rather than the Desktop metaphor.

This is not to say that the Desktop metaphor is superior to the Tools metaphor. The Desktop metaphor targets office automation and publishing. It might not suit other applications (such as software development). However, we could argue that orienting users toward their data rather than toward application programs and employing analogies with the physical world are useful techniques in any domain.

The disadvantage of assigning data files to applications is that users sometimes want to operate on a file with a program other than its “assigned” application. Such cases must be handled in Star in an ad hoc way, whereas systems like Unix allow you to run almost any file through a wide variety of programs. Star’s designers feel that, for its audience, the advantages of allowing users to forget about programs outweighs this disadvantage.

Generic commands. One way to simplify a computer system is to reduce the number of commands. Star achieves simplicity without sacrificing functionality by having a small set of generic commands apply to all types of data: Move, Copy, Open, Delete, Show Properties, and Same (Copy Properties). Dedicated function keys on Star’s keyboard invoke these commands. Each type of data object interprets a generic command in a way appropriate for it.

Such an approach avoids the proliferation of object-specific commands and/or command modifiers found in most systems, such as Delete Character, Delete Word, Delete Line, Delete Paragraph, and Delete File. Command modifiers are necessary in systems in which selection is only approximate. Consider the many systems in which the object of a command is specified by a combination of the cursor location and the command modifier. For example, Delete Word means “delete the word that the cursor is on.”

Modifiers are unnecessary in Star because exact selection of the objects of commands is easy. In many systems, the large number of object-specific commands is made even more confusing by using single-word synonyms instead of command modifiers for similar operations on different objects. For example, depending upon whether the object of the command is a file or text, the command used might be Remove or Delete, Duplicate or Copy, and Find or Search, respectively.

Careful choice of the generic commands can further reduce the number of commands required. For example, you might think it necessary to have a generic command Print for printing various things. Having Print apply to all data objects would avoid the trap that some systems fall into of having separate commands for printing documents, spreadsheets, illustrations, directories, etc., but it is nonetheless unnecessary. In Star, users simply Copy to a printer icon whatever they want to print. Similarly, the Move command is used to invoke Send Mail by moving a document to the out-basket.

Of course, not everything can be done via generic commands. Some operations are object-specific. For example, a word might use italics, but italics are meaningless for a triangle. In Star, object-specific operations are provided via selection-dependent “soft” function keys and via menus attached to application windows.

Direct manipulation and graphical user interface. Traditional computer systems require users to remember and type a great deal just to control the system. This impedes learning and retention, especially by casual users. Star’s designers favored an approach emphasizing recognition over recall, seeing and pointing over remembering and typing. This suggested using menus rather than commands. However, the designers wanted to go beyond a conventional menu-based approach. They wanted users to feel that they are manipulating data directly, rather than issuing commands to the system to do it. Star’s designers also wanted to exploit the tremendous communication possibilities of the display. They wanted to move away from strictly verbal communication. Therefore, they based the system heavily upon principles that are now known as direct manipulation and graphical control.

Star users control the system by manipulating graphical elements on the screen, elements that represent the state of the system and data created by users. The system does not distinguish between input and output. Anything displayed (output) by the system can be pointed to and acted upon by the user (input). When Star displays a directory, it (unlike MS-DOS and Unix) is not displaying a list of the names of the files in the directory, it is displaying the files themselves so that the user can manipulate them. Users of this type of system have the feeling that they are operating upon the data directly, rather than through an agent – like fetching a book from a library shelf yourself rather than asking someone to do it for you.

A related principle is that the state of the system always shows in the display. Nothing happens “behind the user’s back.” You needn’t fiddle with the system to understand what’s going on; you can understand by inspection.

One of Star’s designers wrote

When everything in a computer system is visible on the screen, the display becomes reality. Objects and actions can be understood purely in terms of their effects upon the display. This vastly simplifies understanding and reduces learning time.2

An example of this philosophy is the fact that, unlike many window-based computer systems (even some developed at Xerox), Star has no hidden menus – all available menus are marked with menu buttons.

For a more detailed explanation of direct manipulation, see the sidebar.

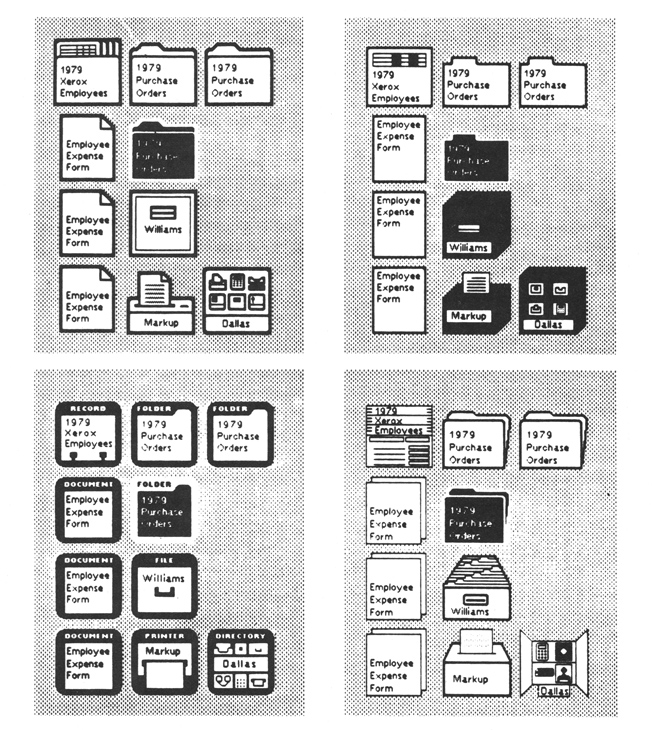

Icons and iconic file management. Computer users often have difficulty managing their files. Before Star existed, a secretary at Xerox complained that she couldn’t keep track of the files on her disk. An inspection of her system revealed files named memo, memol, memo071479, letter, etc. Naming things to keep track of them is bothersome enough for programmers, but completely unnatural for most people.

Star alleviates this problem partly by representing data files with pictures of office objects called icons. Every application data file in the system has an icon representing it. Each type of file has a characteristic icon shape. If a user is looking for a spreadsheet, his or her eye can skip over mailboxes, printers, text documents, etc.

Furthermore, Star allows users to organize files spatially rather than by distinctive naming. Systems having hierarchical directories, such as Unix and MS-DOS, provide an abstract sort of “spatial” file organization, but Star’s approach is concrete. Files can be kept together by putting them into a folder or simply by clumping them together on the Desktop, which models how people organize their physical worlds. Since data files are represented by icons, and files are distinguished by location and specified by selection rather than by name, users can use names like memo, memol, letter, etc., without losing track of their files as easily as they would with most systems.

As bitmap-, window-, and mouse-based systems have become more common, the use of the term “icon” has widened to refer to any nontextual symbol on the display. In standard English, “icon” is a term for religious statues or pictures believed to contain some of the powers of the deities they represent. It would be more consistent with its normal meaning if “icon” were reserved for objects having behavioral and intrinsic properties. Most graphical symbols and labels on computer screens are therefore not icons. In Star, only representations of files on the Desktop and in folders, mailboxes, and file drawers are called icons.

Few modes. A system has modes if user actions differ in effects or availability in different situations. Tesler has argued that modes in interactive computer systems are undesirable because they restrict the functions available at any given point and force users to keep track of the system’s state to know what effect their actions will have.3 Though modes can be helpful in guiding users through unfamiliar procedures or for handling exceptional activities, they should be used sparingly and carefully.

Star avoids modes in several ways. One is the extensive use of generic commands (see above), which drastically reduces the number of commands needed. This, in turn, means that designers need not assign double-duty (that is, different meanings in different modes) to physical controls.

A second way is by allowing applications to operate simultaneously. When using one program (such as a document editor), users are not in a mode that prevents them from using the capabilities of other programs (such as the desktop manager).

A third way Star avoids modes is by using a noun-verb command syntax. Users select an operand (such as a file, a word, or a table), then invoke a command. In conventional systems, arguments follow commands, either on a command line or in response to prompts. Whether a system uses noun-verb or verb-noun syntax has a lot to do with how moded it is. In a noun-verb system such as Star, selecting an object prior to choosing a command does not put the system into a mode. Users can decide not to invoke the command without having to “escape out” of anything or can select a different object to operate on.

Though Star avoids modes, it is not completely modeless. For example, the Move and Copy commands require two arguments: the object to be moved and the final destination. Though less moded ways to design Move and Copy exist, these functions currently require the user to select the object, press the Move or Copy key, then indicate the destination using the mouse. While Star waits for the user to point to a destination, it is in Move or Copy mode, precluding other uses of the mouse. These modes are relatively harmless, however, because (1) the shape of the cursor clearly indicates the state of the system and (2) the user enters and exits them in the course of carrying out a single mental plan, making it unlikely that the system will be in the “wrong” mode when the user begins his or her next action.

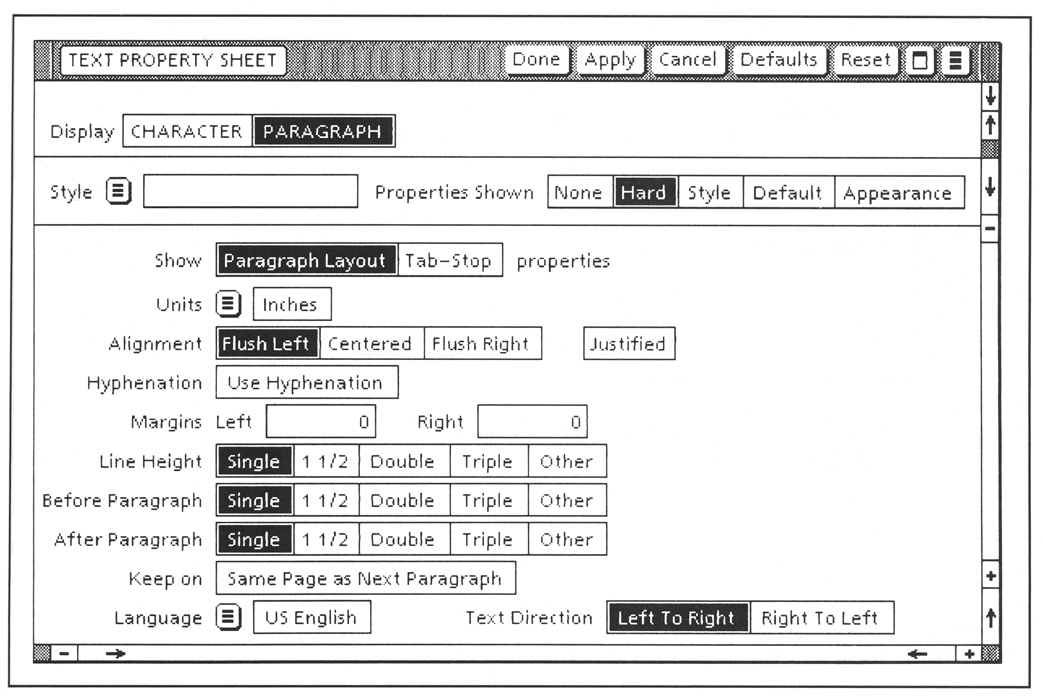

Objects have properties. Properties allow objects of the same type to vary in appearance, layout, and behavior. For example, files have a Name property, characters have a Font family property, and paragraphs have a Justified property. Properties may have different types of values: the Name property of a file is a text string; the Size property of a character might be a number or a choice from a menu; the Justified property of a paragraph is either “on” or “off.” In Star, properties are displayed and changed in graphical forms called property sheets.

Property-based systems are rare. Most computer systems, even today, allow users to set parameters for the duration of an interactive session or for the duration of a command, but not for particular data objects. For example, headings in Wordstar documents do not “remember” whether they are centered or not; whether a line is centered is determined by how the program was set when the line was typed. Similarly, directories in Unix do not “remember” whether files are to be listed in alphabetical or temporal order; users must respecify which display order they want every time they invoke the ls command.

Progressive disclosure. It has been said that “computers promise the fountains of Utopia, but only deliver a flood of information.”4 Indeed, many computer systems overwhelm their users with choices, commands to remember, and poorly organized output, much of it irrelevant to what the user is trying to do. They make no presumptions about what the user wants. Thus, they are designed as if all possible user actions were equally likely and as if all information generated by the system were of equal interest to the user. Some systems diminish the problem somewhat by providing default settings of parameters to simplify tasks expected to be common.

Star goes further towards alleviating this problem by applying a principle called “progressive disclosure.” Progressive disclosure dictates that detail be hidden from users until they ask or need to see it. Thus, Star not only provides default settings, it hides settings that users are unlikely to change until users indicate that they want to change them. Implicit in this design are assumptions about which properties will be less frequently altered.

One place progressive disclosure is used is in property sheets. Some objects have a large number of properties, many of which are relevant only when other properties have certain values (see Figure 2). For example, on the page layout property sheet, there is no reason to display all of the properties for specifying running header content and position unless the user actually specifies that the document will have running headers.

Another example of progressive disclosure is the fact that property displays in Star are temporary, displayed on demand. In some systems, the properties of the current selection are displayed at all times, through codes embedded in the text or in an area of the screen reserved for that purpose, even though the user usually doesn’t care.

A highly refined manifestation of progressive disclosure recently added to ViewPoint is styles, which allows users to regard document content (such as a paragraph) as having a single style rule instead of a large number of properties. Thus, styles hide needless detail from users.

Consistency. Because Star and all of its applications were designed and developed in-house, its designers had more control over its user interface than is usually the case with computer systems. Because the designers paid close attention to detail, they achieved a very high degree of consistency. The left mouse button always selects; the right always extends the selection. Mouse-sensitive areas always give feedback when the left button goes down, but never take effect until the button comes up.

Emphasis on good graphic and screen design. Windows, icons, and property sheets are useless if users can’t easily distinguish them from the background or each other, can’t easily see which labels correspond to which objects, or can’t cope with the visual clutter. To assure that Star presents information in a maximally perceivable and useful fashion, Xerox hired graphic designers to determine the appearance and placement of screen objects. These designers applied various written and unwritten principles to the design of the window headers and borders, the Desktop background, the command buttons, the pop-up menus, the property sheets, and the Desktop icons. The most important principles are

The illusion of manipulable objects. One goal, fundamental to the notion of direct manipulation, is to create the illusion of manipulable objects. It should be clear that objects can be selected and how to select them. It should be obvious when they are selected and that the next action will apply to them. Whereas the usual task of graphic designers is to present information for passive viewing, Star’s designers had to figure out how to present information for manipulation as well. This shows most clearly in the Desktop icons, with their clear figure/ground relationship: the icons stand by themselves, with self-contained labels. Windows reveal in their borders the “handles” for scrolling, paging, window-specific commands, and pop-up menus.

Visual order and user focus. One of the most obvious contributions of good graphic design is appropriate visual order and focus on the screen. For example, intensity and contrast, when appropriately applied, draw the user’s attention to the most important features of the display.

In some windowing systems, window interiors have the same (dark) color as the Desktop background. Window content should have high intensity relative to the Desktop, to draw attention to what is important on the screen. In Star, window content background is white, both for high contrast and to simulate paper.

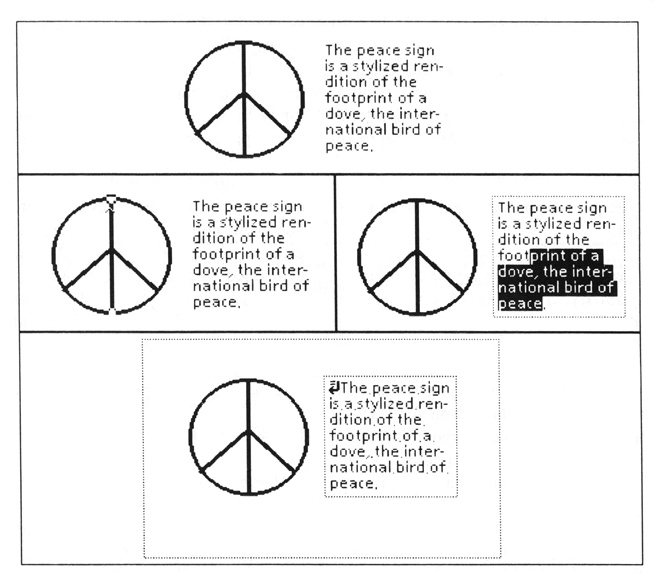

Star keeps the amount of black on the screen to a minimum to make the selection stand out (see Figure 3). In most windowing systems, window headers and other areas of the screen are black, making the selection hard to find. This principle is so important that Star’s designers made sure that the display hardware could fill the nonaddressable border of the screen with Desktop grey rather than leaving it black as in most systems. Star also uses icon images that turn from mostly white to mostly black when selected (see Figure 4) and allows at most one selection on the screen at a time.

Revealed structure. Often, the more powerful the program used, the greater the distance between intention and effect. If only effect is displayed and not intention, the user’s task of learning the connection is much more difficult. A good graphical interface can make apparent to the user these connections between intention and effect, that is, “revealed structure.” For example, there are many ways to determine the position and length of a line of text on a page. It can be done with page margins, paragraph indentations, centering, tabs, blank lines, or spaces. The WYSIWYG, or “what you see is what you get,” view of all these would be identical. That would be enough if all that mattered to the user was the final form on paper. But what will happen if characters are inserted? If the line is moved to another page, where will it land? WYSIWYG views are sometimes not enough.

Special views are one method of revealing structure. In Star, documents can show “Structure” and/or “Non-Printing Characters” if desired (see Figure 5). Another convenient means for revealing structure is to make it show up during selection. For example, when a rectangle is selected in a graphics frame, eight control points highlight it, any of which can attach to the cursor during Move or Copy and can land on grid points for precise alignment. The control point highlighting allows a user to distinguish a rectangle from four straight lines; both might produce the same printed effect but would respond differently to editing.

Consistent and appropriate graphic vocabulary. Property sheets (see Figure 2) present a form-like display for the user to specify detailed property settings and arguments to commands. They were designed with a consistent graphic vocabulary. All of the user’s targets are in boxes; unchangeable information such as a property name is not. Mutually exclusive values within choice parameters appear with boxes adjacent. Independent “on/off” or state parameters appear with boxes separated. The current settings are shown inverted. Some of the menus display graphic symbols rather than text. Finally, there are text parameters consisting of a box into which text or numbers can be typed, copied, or moved, and within which text editing functions are available.

Match the medium. It is in this last principle that the sensitivities of a good graphic designer are most apparent. The goal is to create a consistent quality in the graphics that is appropriate to the product and makes the most of the given medium. Star has a large black and white display. The solutions the graphics designers devised might have been very different had the display had grey-scale or color pixels.

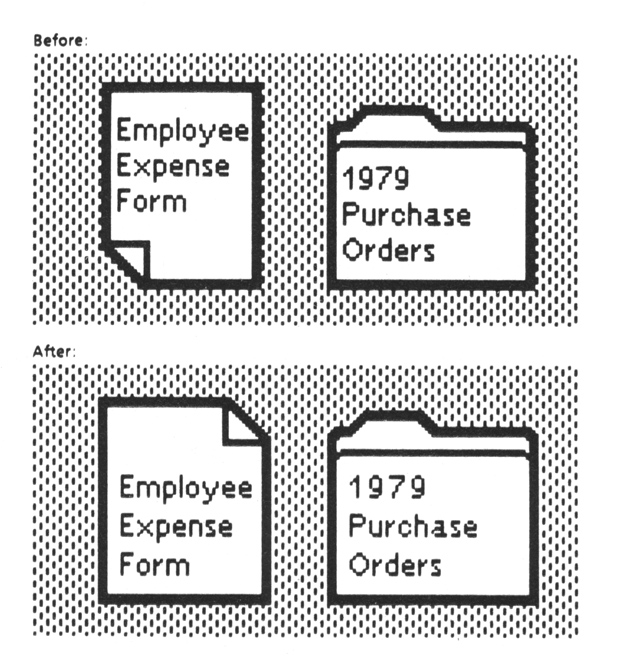

A common problem with raster displays is “jaggies”: diagonal lines appearing as staircases. With careful design, jaggies can be avoided, for example, by using only vertical, horizontal, and 45-degree angles. Also important is controlling how the edges of the figures interact with the texture of the ground. Figure 6 shows how edges are carefully matched to the background texture so that they have a consistent quality appearance.

Document editor level

At the top level of Star’s architecture are its applications, the most prominent of which is the document editor.

WYSIWYG document editor. Within the limits of screen resolution, Star documents are displayed as they will print, including typographic features such as boldface, italics, proportional spacing, variable font families, and superscripts, and layout features such as embedded graphics, page numbers, headers, and footers. This is commonly referred to as “what you see is what you get,” or WYSIWYG.

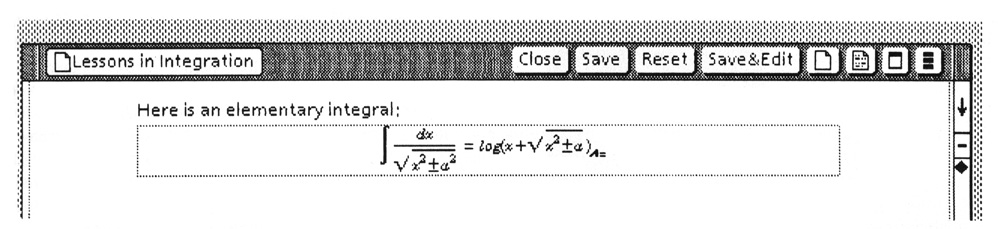

Star adheres to this principle even in domains where other WYSIWYG document editors do not. For example, mathematical formulas are created and edited in documents using a WYSIWYG editor that has knowledge built into it about the appearance and layout of mathematical symbols. A square root sign has a slot for an expression and grows when the expression becomes large (see Figure 7). In most systems, mathematical formulas are created either by putting together special characters to make mathematical symbols or by using a special in-line notation (such as sqrt(sigma(l, n, (x*3)/2))) to represent the formula that will eventually be printed. Formulas created with such systems usually require several print-edit cycles to get right.

Extended character set for multilingual capability. Star uses 16-bit character codes, in contrast to most of the computer industry, which uses seven- or eight-bit character codes (for example, ASCII or EBCDIC). The Star character set is a superset of ASCII. The reason for a 16-bit code is a strong market requirement for enhanced multilingual capability coming from Xerox’s subsidiaries in Europe and Japan. Most systems provide non-English characters through different fonts, so that the eight-bit “extended” ASCII codes might be rendered as math symbols in one font, Greek letters in another font, and Arabic in yet another. This has the effect that when any application loses track of font information while handling the text (which happens often in some systems), a paragraph of Arabic may turn into nonsensical Greek or math symbols or something else, and vice versa.

Star uses 16-bit character codes to permit the system to reliably handle European languages and Japanese, which uses many thousands of characters. All Star and ViewPoint systems have French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Russian language capabilities built in. The Japanese language capability was developed as part of the original Star design effort and released in Japan soon after Star’s debut in the United States. Since that time, many more characters have been added, covering Chinese, Arabic, Hebrew, and nearly all European languages.

As explained in several articles by Joe Becker, the designer of Star’s multilingual capabilities, handling many of the world’s languages requires more than an expanded character set.5 Clever typing schemes and sophisticated rendering algorithms are required to provide a multilingual capability that satisfies customers.

The document is the heart of the world and unifies it. Most personal computers and workstations give no special status to any particular application. Dozens of applications are available, most incompatible with each other in data format as well as user interface.

Star, in contrast, assumes that the primary use of the system is to create and maintain documents. The document editor is thus the primary application. All other applications exist mainly to provide or manipulate information whose ultimate destination is a document. Thus, most applications are integrated into the document editor (see “Integrated applications” above), operating within frames embedded in documents. Those applications that are not part of the document editor support transfer of their data to documents.

History of Star development

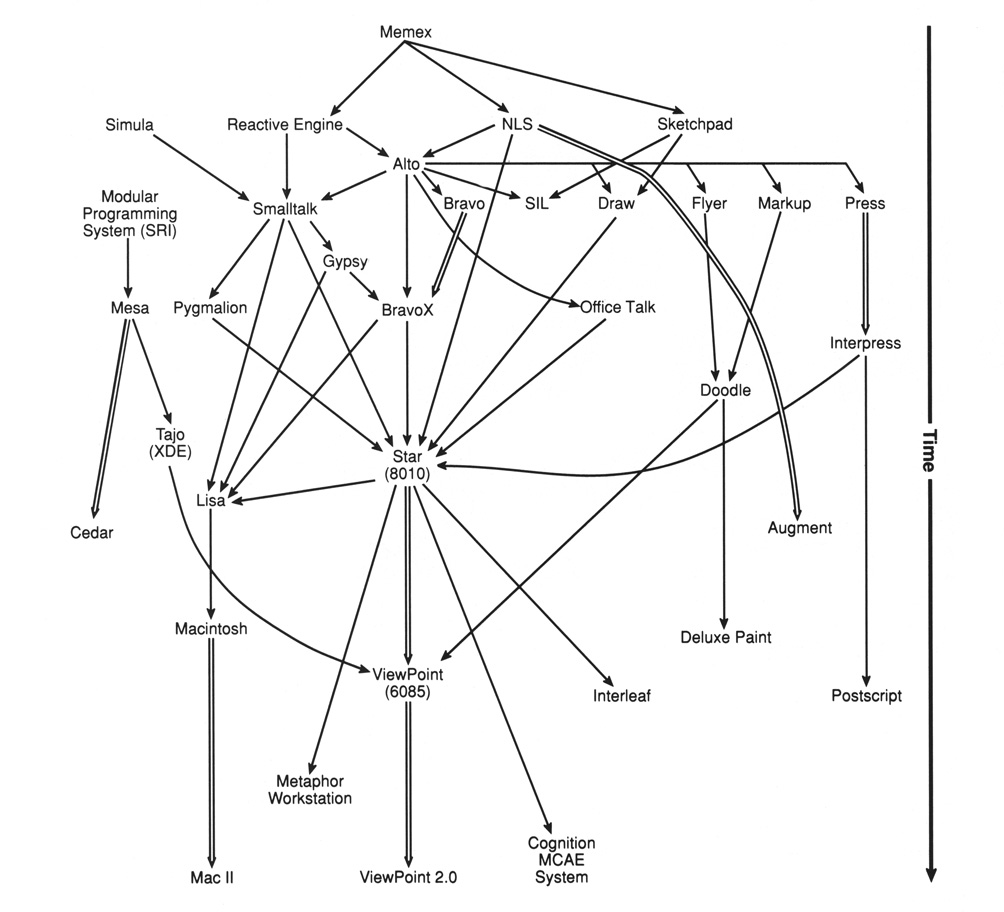

Having described Star and ViewPoint, we will describe where they came from and how they were developed. Figure 8 graphs this history, showing systems that influenced Star and those influenced by it.

Pre-Xerox

Although Star was conceived as a product in 1975 and was released in 1981, many of the ideas that went into it were born in projects dating back more than three decades.

Memex. The story starts in 1945, when Vannevar Bush, a designer of early calculators and one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s science advisors, wrote an article describing his vision of the uses of electronics and information technology. At a time when computers were new, room-sized, and used only for military number-crunching, Bush envisioned a personal, desktop computer for non-numerical applications. He called it the Memex. Due to insufficient technology and insufficient imagination on the part of others, Bush’s ideas languished for 15 years.

Sketchpad. In the sixties, people began to take interactive computing seriously. One such person was Ivan Sutherland. He built an interactive graphics system called Sketchpad that allowed a user to create graphical figures on a CRT display using a light pen. The geometric shapes users put on the screen were treated as objects: after being created, they could be moved, copied, shrunk, expanded, and rotated. They could also be joined together to make larger, more complex objects that could then be operated upon as units. Sketchpad influenced Star’s user interface as a whole as well as its graphics applications.

NLS. Also in the sixties, Douglas Engelbart established a research program at Stanford Research Institute (now called SRI International) for exploring the use of computers “to augment the knowledge worker” and human intellect in general. He and his collegues experimented with different types of displays and input devices (inventing the mouse when other pointing devices proved inadequate) and developed a system commonly known as NLS. (The actual name of the system was On-Line System. A second system called Off-Line System was abbreviated FLS, hence NLS’s strange abbreviation. NLS is now marketed by McDonnell Douglas under the name Augment.)

NLS was unique in several respects. It used CRT displays when most computers used teletypes. It was interactive (i.e., online) when almost all computing was batch. It was full-screen-oriented when the few systems that were interactive were line-oriented. It used a mouse when all other graphic interactive systems used cursor keys, light pens, joysticks, or digitizing tablets. Finally, it was the first system to organize textual and graphical information in trees and networks. Today, it would be called an “idea processor” or a “hypertext system.”

The Reactive Engine. While Engelbart et al. were developing ideas, some of which eventually found their way into Star, Alan Kay, then a graduate student, was doing likewise. His dissertation, The Reactive Engine, contained the seeds of many ideas that he and others later brought to fruition in the Smalltalk language and programming environment, which, in turn, influenced Star. Like the designers of NLS, Kay realized that interactive applications do not have to treat the display as a “glass teletype” and can share the screen with other programs.

Xerox PARC

In 1970, Xerox established a research center in Palo Alto to explore technologies that would be important not only for the further development of Xerox’s then-existing product line (copiers), but also for Xerox’s planned expansion into the office systems business. The Palo Alto Research Center was organized into several laboratories, each devoted to basic and applied research in a field related to the above goals. The names and organization of the labs have changed over the years, but the research topics have stayed the same: materials science, laser physics, integrated circuitry, computer-aided design and manufacturing, user interfaces (not necessarily to computers), and computer science (including networking, databases, operating systems, languages and programming environments, graphics, document production systems, and artificial intelligence).

Alto. PARC researchers were fond of the slogan “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” After some initial experiments with time-shared systems, they began searching for a new approach to computing.

Among the founding members of PARC was Alan Kay. He and his colleagues were acquainted with NLS and liked its novel approach to human-computer interaction. Soon, PARC hired several people who had worked on NLS. In 1971, the center signed an agreement with SRI licensing Xerox to use the mouse. Kay and others were dedicated to a vision of personal computers in a distributed environment. In fact, they coined the term “personal computer” in 1973, long before microcomputers started what has been called the “personal computer revolution.”

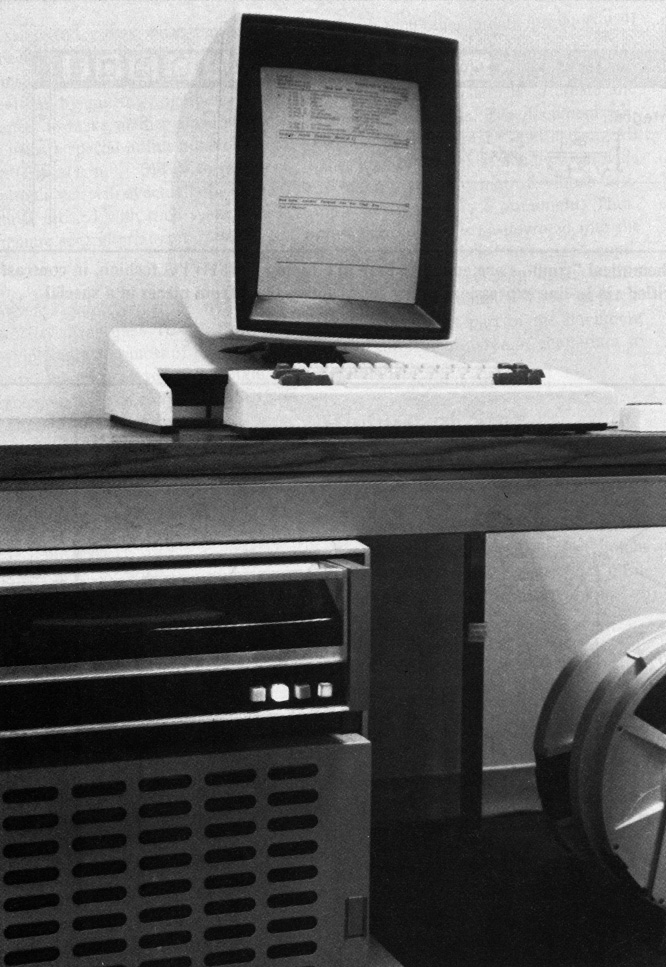

One result of the search for a new approach was the Alto (see Figure 9). The Alto was a minicomputer that had a removable, 2.5-megabyte hard disk pack (floppy disks did not exist at the time) and 128 to 256 kilobytes of memory. Unlike most machines of its day, the Alto also had a microprogrammable instruction set, a “full-page” (10½ × 8¼ inch, 600 × 800 pixel) bitmapped graphic display, about 50 kilobytes of high-speed display memory, and a mouse.

The first Alto became operational in 1972. At first, only a half-dozen or so Altos were built. After software that exploited the Alto’s capabilities became available, demand for them grew tremendously, spreading beyond PARC into Xerox as a whole and even to external customers. Eventually, Xerox built more than a thousand Altos.

Ethernet. Another product of the new approach was the Ethernet. With its standardized, layered communications protocols, Ethernet provided a way of connecting computers much more flexibly than previously possible. Soon after the first Altos were built, they were networked together. Eventually, the network grew to thousands of workstations (Altos and Alto successors) within Xerox’s worldwide organization.

Smalltalk. Alan Kay was one of the main advocates of the Alto. His Learning Research Group began using the Alto to build prototypes for a personal computing system “of the future” – a portable machine that would provide not canned applications but rather the building blocks necessary for users to build the tools and applications they needed to solve their own information processing problems. The technologies needed to build a lap computer with the power of the envisioned system (called the “DynaBook”) were unavailable at the time and still are.

The prototypes developed by Kay’s group evolved into the Smalltalk language and programming environment. Smalltalk further promoted the notion of personal computing; pioneered complete, interactive programming environments; and refined and solidified concepts of object-oriented programming that had been extant only in vestigial forms in previous systems. Most importantly for Star, Smalltalk demonstrated the power of graphical, bitmapped displays; mouse-driven input; windows; and simultaneous applications. This is the most visible link between Smalltalk and Star, and is perhaps why many people wrongly believe that Star was written in Smalltalk.

Pygmalion. The first large program to be written in Smalltalk was Pygmalion, the doctoral thesis project of David C. Smith. One goal of Pygmalion was to show that programming a computer does not have to be primarily a textual activity. It can be accomplished, given the appropriate system, by interacting with graphical elements on a screen. A second goal was to show that computers can be programmed in the language of the user interface, that is, by demonstrating what you want done and having the computer remember and reproduce it. The idea of using icons – images that allow users to manipulate them and in so doing act upon the data they represent – came mainly from Pygmalion. After completing Pygmalion, Smith worked briefly on the NLS project at SRI before joining the Star development team at Xerox.

Bravo, Gypsy, and BravoX. At the same time that the Learning Research Group was developing Smalltalk for the Alto, others at PARC, mainly Charles Simonyi and Butler Lampson, were writing an advanced document editing system for it called Bravo. Because it made heavy use of the Alto’s bitmapped screen, Bravo was unquestionably the most WYSIWYG text editor of its day, with on-screen underlining, boldface, italics, variable font families and sizes, and variable-width characters. It allowed the screen to be split, so different documents or different parts of the same document could be edited at once, but did not operate in a windowed environment as we use the term today. Bravo was widely used at PARC and in Xerox as a whole.

From 1976 to 1978, Simonyi and others rewrote Bravo, incorporating many of the new user-interface ideas floating around PARC at the time. One such idea was modelessness, promoted by Larry Tesler3 and exemplified in Tester’s prototype text editor, Gypsy. Simonyi et al. also added styles, enhancing users’ ability to control the appearance of their documents. The new version was called BravoX.

Shortly thereafter, Simonyi joined Microsoft, where he led the development of Microsoft Word, a direct descendent of BravoX. Another member of the BravoX team, Tom Malloy, went to Apple and wrote LisaWrite.

Draw, Sil, Markup, Flyer, and Doodle. Star’s graphics capability (its provisions for users to create graphical images for incorporation into documents, as opposed to its graphical user interface) owes a great deal to several graphics editors written for the Alto and later machines.

Draw, by Patrick Beaudelaire and Bob Sproull, and Sil (for Simple Illustrator) were intellectual successors of Sutherland’s Sketchpad (see above): graphical object editors that allowed users to construct figures out of selectable, movable, stretchable geometric forms and text. In turn, Star’s graphic frames capability is in large measure an intellectual successor of Draw and Sil.

Markup was a bitmap graphics editor (that is, a paint program) written by William Newman for the Alto. Flyer was another paint program, written in Smalltalk for the Alto by Bob Flegel and Bill Bowman. These programs inspired Doodle, a paint program written for a later machine by Dan Silva. Doodle eventually evolved into Viewpoint’s Free-Hand Drawing application. Silva went on to write De-luxePaint, a paint program for PCs.

Laser printing. Fancy graphics capabilities in a workstation are of little use without hard-copy capability to match it. Laser printing, invented at PARC, provided the necessary base capability, but computers needed a uniform way to describe output to laser printers. For this purpose, Bob Sproull developed the Press page-description language. Press was heavily used at PARC, then further developed into Interpress, Xerox’s commercial page-description language and the language in which Star encodes printer output. Some of the developers of Interpress later formed Adobe Systems and developed Postscript, a popular page description language.

Laurel and Hardy. A network of personal workstations suggests electronic mail. Though electronic mail was not invented at PARC, PARC researchers (mainly Doug Brotz) made it more accessible to nonengineers by creating Laurel, a display-oriented tool for sending, receiving, and organizing e-mail. The experience of using Laurel inspired others to write Hardy for an Alto successor machine. Laurel and Hardy were instrumental in getting nonengineers at Xerox to use e-mail. The use of e-mail spread further with the spread of Star and ViewPoint throughout Xerox.

OfficeTalk. One more Alto program that influenced Star was OfficeTalk, a prototype office automation system written by Clarence (“Skip”) Ellis and Gary Nutt. OfficeTalk supported standard office automation tasks and tracked jobs as they went from person to person in an organization. Experience with OfficeTalk provided ideas for Star because of the two systems’ similar target applications.

Summing up. The debt that Star owes to the Alto and its software is best summed up by quoting from the original designers, who wrote in 1982:

Alto served as a valuable prototype for Star… Alto users have had several thousand work-years of experience with them over a period of eight years, making Alto perhaps the largest prototyping effort in history. There were dozens of experimental programs written for the Alto by members of the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. Without the creative ideas of the authors of these systems, Star in its present form would have been impossible… In addition, we ourselves programmed various aspects of the Star design on the Alto…

Star

To develop Star and other office systems products, Xerox created the Systems Development Department. SDD was staffed by transferring people from other parts of Xerox, including PARC, as well as by hiring from outside. Thus, contrary to what has often been stated in the industry press, Star was not developed at PARC, but rather in a separate product-development organization.

When SDD was formed, a decision was made to use Mesa, an “industrial-strength” dialect of Pascal conceived at SRI and further developed at PARC, as the primary product programming language. SDD took over development and maintenance of Mesa from the Computer Science Laboratory at PARC, freeing CSL to develop Mesa’s research successor, Cedar.

Star hardware. Star is often discussed as if it were a computer. In fact, Star is a body of software. (The official name for Star was the Xerox 8010 Information System. The machine was called the 8000 Series Network Systems Processor. Originally, “Star” was only an internal name.) However, using the name Star to refer to the machine is understandable since the machine was designed in conjunction with the software to meet the needs of the software design. This is in sharp contrast to the usual approach, in which software is designed for existing computers.

The 8000 Series workstation was based upon a microcoded processor designed within Xerox especially to run the object code produced by the Mesa compiler. Besides being microprogrammed to run Mesa, the processor provided low-level operations for facilitating display operations. For example, the bitblt operation for manipulating rectangular arrays of screen pixels is implemented as a single instruction. As sold, the machine was configured with at least 384 kilobytes of real memory (expandable to 1.5 megabytes), a local hard disk (10, 29, or 40 megabytes), a 17-inch display, a mechanical mouse, an eight-inch floppy disk drive, and an Ethernet connection. The price was initially $16,500 with software.

Even though the machine was designed to run Star, it also ran other software. In addition to selling it as the 8010 “Star” workstation, Xerox sold it as a server machine and as an Interlisp and a Smalltalk workstation.

Star software. Alhough Star incorporated ideas from a number of predecessors, it still required a mammoth design effort to pull all of those ideas – as well as new ideas – together to produce a coherent design. According to the original designers, “…it was a real challenge to bring some order to the different user interfaces on the Alto.”1 About 30 person-years went into the design of the user interface, functionality, and hardware.

To foster uniformity of specifications as well as thoughtful and uniform design, Star’s designers developed a strict format for specifications. Applications and system features were to be described in terms of the objects that users would manipulate with the software and the actions that the software provided for manipulating objects. This “objects and actions” analysis was supposed to occur at a fairly high level, without regard to how the objects would actually be presented or how the actions would actually be invoked by users. A full specification was then written from the “objects and actions” version. This approach forced designers to think clearly about the purpose of each application or feature and fostered recognition of similar operations across specifications, allowing what might have seemed like new operations to be handled by existing commands.

When SDD was formed, it was split between two locations: Southern California (El Segundo) and Northern California (Palo Alto). Few people were willing to transfer one way or the other, leaving SDD with the choice of losing many competent engineers or being creative. SDD’s management took the creative route: they put the Ethernet to work, attaching the development machines at both sites to a network, connecting the two sites with a 56-kilobit-per-second leased line, encouraging heavy use of electronic mail for work-related communication, and developing tools for facilitating distributed, multiparty development.

As might be expected from Star’s origins, most of the design and prototyping work was done in Palo Alto, whereas most of the implementation was done in El Segundo. Though this split was handled creatively, some of Star’s designers now believe it caused problems not overcome by extensive use of e-mail. For example, the implementors did not benefit from much of the prototyping done at PARC.

The development process has been recounted in detail elsewhere6 and will not be repeated here. Suffice it to say that the Star development effort

- involved developing new network protocols and data-encoding schemes when those used in PARC’s research environment proved inadequate;

- involved a great deal of prototyping and user testing;

- included a late redesign of the processor;

- included several software redesigns, rewrites, and late additions, some based on results from user testing, some based on marketing considerations, and some based on systems considerations (see below);

- included a level of attention to the requirements of international customers unmatched in the industry; and

- left much of what was in the Star Functional Specification unimplemented.

Tajo/XDE

Since the machine upon which Star ran was developed in parallel with the software, it was not available early-on for use as a software development platform. Early prototyping and development was done on Altos and successor research machines developed at PARC. Though the Mesa language ran on these machines, development aids for Mesa programmers were lacking.

When the 8000 Series workstation became available, the systems group within SDD began working on a suitable development environment. Known internally as Tajo and externally as Xerox Development Environment (XDE), the completed development environment and the numerous tools written to run in it were quickly adopted by programmers throughout SDD. Star’s later improvements adopted many good ideas from Tajo.

ViewPoint

Though Star’s introduction at NCC ’81 was lauded in the industry press, initial sales were not what had been hoped. Almost immediately, efforts were launched to improve its performance, extensibility, maintainability, and cost.

ViewPoint software. Even before Star was released, the implementors realized that it had serious problems from their point of view. Its high degree of integration and user-interface consistency had been achieved by making it monolithic: the system “knew” about all applications, and all parts of the system “knew” about all other parts. It was difficult to correct problems, add new features, and increase performance. The monolithic architecture also did not lend itself to distributed, multiparty development.

This created pressure to rewrite Star. Bob Ayers, who had been heavily involved in the development of Star, rewrote the infrastructure of the system according to the more flexible Tajo model. He built, on top of the operating system and low-level window manager, a “toolkit” for building Star-like applications.

In the new infrastructure, transfer of data between different applications was handled through strict protocols involving the user’s selection, thus making applications independent from one another. The object-oriented user interface, which requires that the system associate applications with data files, was preserved by having applications register themselves with the system when started, telling it which type of data file they correspond to and registering procedures for handling keyboard and mouse events and generic commands. User-interface consistency was fostered by building many of the standards into the application toolkit. The development organization completed the toolkit and then ported or rewrote the existing applications and utilities to run on top of it.

Other software changes included

- the addition of several applications and utilities, including a Free-Hand Drawing program and an IBM PC emulation application;

- optional window tiling constraints, so that users can have overlapping windows if desired;

- redesigned screen graphics (icons, windows, property sheets, command buttons, and menus) to accommodate a smaller screen and to meet the demands of a more sophisticated public; and

- improved performance.

To underscore the fact that the new system was a substantial improvement over the old, the name was changed from Star to ViewPoint. ViewPoint 1.0 was released in 1985.

ViewPoint hardware. In addition to revising the software, Xerox brought the hardware up to date by designing a completely new vehicle for ViewPoint: the 6085 workstation. The new machine was designed to take advantage of advances in integrated circuitry, reductions in memory costs, new disk technologies, and new standards in keyboard design, as well as to provide IBM PC compatibility. The 6085 workstation has a Mesa processor plus an optional IBM-PC-compatible processor, one megabyte of real memory (expandable to 4 megabytes), a hard disk (10 to 80 megabytes), a choice of a 15- or a 19-inch display, an optical mouse, a new keyboard, a 5¼-inch floppy disk drive, and, of course, an Ethernet connection. The base cost was initially $6,340 with the ViewPoint software. Like the 8010, the 6085 is sold as a vehicle for Interlisp and Smalltalk as well as for ViewPoint.

Recent ViewPoint changes. The recently released ViewPoint 2.0 adds many features relevant to desktop publishing. These include

- Xerox ProIllustrator, a new vector graphics editing application designed mainly for professional illustrators;

- Shared Books, support for groups of users working on multipart documents;

- a Redlining feature, for tracking deletions and insertions in documents;

- cursor keys, for moving the insertion point during keyboard-intensive work; and

- stylesheets, for facilitating control of document appearance.

Lessons from experience

So what have we learned from all this? We believe, the following:

Pay attention to industry trends.

Partly out of excitement over what they were doing, PARC researchers and Star’s designers didn’t pay enough attention to the “other” personal computer revolution occurring outside of Xerox. By the late seventies, Xerox had its own powerful technical tradition (mouse-driven, networked workstations with large bitmapped screens and multiple, simultaneous applications), blinding Star’s designers to the need to approach the market with cheap, stand-alone PCs. The result was a product that was highly unfamiliar to its intended customers: businesses. Nowadays, of course, such systems are no longer unusual.

Developing Star and ViewPoint involved developing several enabling technologies, for networking, communicating with servers, describing pages to laser printers, and developing software. At the time they were developed, these technologies were unique in the industry. Xerox elected to keep them proprietary for fear of losing its competitive advantage. With hindsight, we can say that it might have been better to release these technologies into the public domain or to market them early, so that they might have become industry standards. Instead, alternative approaches developed at other companies have become the industry standards. Xerox’s current participation in the development of various industry standards indicates its desire to reverse this trend.

Pay attention to what customers want.

The personal computer revolution has shown the futility of trying to anticipate all of the applications that customers will want. Star should have been designed from the start to be open and extensible by users, as the Alto was. In hindsight, extensibility was one of the keys to the Alto’s popularity. The problem wasn’t that Star lacked functionality, it was that it didn’t have the functionality customers wanted. An example is the initial lack of a spreadsheet application. The designers failed to appreciate the significance of this application, which may have been more important even than word-processing in expanding the personal computer revolution beyond engineers and hobbyists into business. Eventually realizing that Star’s closedness was a problem, Xerox replaced it with ViewPoint, a more “open” system that allows users to pick and choose applications that they need, including a spreadsheet and IBM PC software. Apple Computer learned the same lesson with its Lisa computer and similarly replaced it with a cheaper one having a more open software architecture: the Macintosh.

Know your competition.

Star’s initial per-workstation price was near that of time-shared minicomputers, dedicated word-processors, and other shared computing facilities. Star was, however, competing for desktop space with microcomputer-based PCs. ViewPoint has corrected that problem: The 6085 costs about the same as its competition.

Establish firm performance goals.

Star’s designers should have established performance goals, documented them in the functional specifications, and stuck to them as they developed Star. Where performance goals couldn’t be met, the corresponding functionality should have been cut.

In lieu of speed, the designers should have made the user interface more responsive. Designing systems to handle user input more intelligently can make them more responsive without necessarily making them execute functions faster. They can operate asynchronously with respect to user input, making use of background processes, keeping up with important user actions, delaying unimportant tasks (such as refreshing irrelevant areas of the screen) until time permits, and skipping tasks called for by early user actions but rendered moot by later ones. ViewPoint now makes use of background processes to increase its responsiveness.

Avoid geographically split development organizations.

Having a development organization split between Palo Alto and El Segundo was probably a mistake, less for reasons of distance per se than for lack of shared background in “PARC-style” computing. However, the adverse effect of sheer distance on communication was certainly a factor.

Don’t be dogmatic about the Desktop metaphor and direct manipulation.

Direct manipulation and the Desktop metaphor aren’t the best way to do everything. Remembering and typing is sometimes better than seeing and pointing. For example, if users want to open a file that is one of several hundred in a directory (folder), the system should let users type its name rather than forcing them to scroll through the directory trying to spot it so they can select it.

Many aspects of Star were correct.

Though certain aspects of Star perhaps should have been done differently, most of the aspects of Star’s design described at the beginning of this article have withstood the test of time. These include

- Iconic, direct-manipulation, object-oriented user interface. The days of cryptic command languages and scores of commands for users to remember (a la Unix and MS-DOS) should have passed long ago.

- Generic commands and consistency in general. Even Macintosh could use some lessons in this regard: the Duplicate command copies files within a disk, but users must drag icons to copy them across disks and must use Copy-Paste to copy anything else.

- Pointing device. Although cursor keys have some advantages and certainly would have enhanced Star’s market appeal (as they have Viewpoint’s), Star’s designers stand by the system’s primary reliance on the mouse. This does not imply a commitment to the mouse per se, but rather to any pointing device that allows quick pointing and selection. As interfaces evolve in the future, high-resolution touch screens and other more exotic devices may replace mice as the pointing devices of choice.

- High-resolution display. Memory is now cheap, so the justification for character displays is gone.

- Good graphic design. Screen graphics designed by computer programmers will not satisfy customers. The Star designers recognized their limitations in this regard and hired the right people for the job. As color displays gain market presence, the participation of graphic designers will become even more crucial.

- 16-bit character set. An eight-bit character set (such as ASCII) cannot accommodate international languages adequately. Star and Viewpoint’s use of a 16-bit character set and of special typing and rendering algorithms for foreign languages is the correct approach.

- Distributed, personal computing. Though the reorientation of the industry away from batch and time-shared computing toward personal computing had nothing to do with Xerox, PARC, or Star, it was an important part of the computing philosophy that led to Star.

Star has had an indisputable influence on the design of computer systems. For example, the Lisa and Macintosh might have been very different had Apple’s designers not borrowed ideas from Star, as the following excerpt of a Byte magazine interview of Lisa’s designers shows:

Byte: Do you have a Xerox Star here that you work with?

Tesler: No, we didn’t have one here. We went to the NCC [National Computer Conference] when the Star was announced and looked at it. And in fact it did have an immediate impact. A few months after looking at it we made some changes to our user interface based on ideas that we got from it. For example, the desktop manager we had before was completely different; it didn’t use icons at all, and we never liked it very much. We decided to change ours to the icon base. That was probably the only thing we got from Star, I think. Most of our Xerox inspiration was Smalltalk rather than Star.7

Elements of the Desktop metaphor approach also appear in many other systems.

The history presented here has shown, however, that Star’s designers did not invent the system from nothingness. Just as it has influenced systems that came after it, Star was influenced by ideas and systems that came before it. It is difficult to inhibit the spread of good ideas once they are apparent to all, especially in this industry. Star was thus just one step in an evolutionary process that will continue both at Xerox and elsewhere. That is how it should be.

Jeff Johnson and Teresa L. Roberts, US West Advanced Technologies William Verplank, IDTwo David C. Smith, Cognition, Inc. Charles H. Irby and Marian Beard, Metaphor Computer Systems Kevin Mackey, Xerox

Acknowledgments

When Star was announced, several articles on it appeared in trade magazines, journals, and at conferences. Many of these were reprinted in the Xerox publication Office Systems Technology.8 Since then, several more articles have been published that are relevant to this retrospective. They include an article from MacWorld9 that described the historical antecedents of Apple Computer’s Lisa and Macintosh computers, which share much of Star’s history. This retrospective owes a great deal to those previous writings. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions that Joe Becker, Bill Mallgren, Doug Carothers, Linda Bergsteinsson, and Randy Polen of Xerox, and Bob Ayers, Ralph Kimball, Dave Fylstra, and John Shoch made to this retrospective. Finally, we acknowledge the helpful suggestions made by the first and second authors’ colleagues at US West Advanced Technologies and several anonymous reviewers to improve the quality of the article.

References

- D.C. Smith et al., The Star User Interface: An Overview, Proc. AFIPS Nat’l Computer Conf, June 1982, pp. 515-528.

- D.C. Smith, “Origins of the Desktop Metaphor: A Brief History,” presented in a panel discussion, “The Desktop Metaphor as an Approach to User Interface Design,” in Proc. ACM Annual Conf., 1985, p. 548.

- L. Tesler, “The Smalltalk Environment,” Byte, Vol. 6, No. 8, Aug. 1981, pp. 90-147.

- L. Winner, “Mythinformation,” Whole Earth Review, No. 44, Jan. 1985.

- J. Becker, “Multilingual Word Processing,” Scientific American, Vol. 251, No. 1, July 1984, pp. 96-107. (See Further reading for other articles on Star’s multilingual capability.)

- E.F. Harslem and L.E. Nelson, A Retrospective on the Development of Star, Proc. Sixth Int’l Conf. on Software Engineering, Sept. 1982, Tokyo, Japan. Reprinted in Office Systems Technology, OSD-R8203A, Xerox Corp., pp. 261-269.

- G. Williams, The Lisa Computer System, Byte, Vol. 8, No. 2, Feb. 1983, pp. 33-50.

- Office Systems Technology, OSD-R8203A, Xerox Corp.

- T. Nace, “The Macintosh Family Tree,” MacWorld, Nov. 1984, pp. 134-141.

Further Reading

For interested readers, we provide here a guide to further reading on Star and releated topics. A more comprehensive and detailed version of this retrospective will appear in an upcoming Prentice-Hall book series. Also, the September issue of IEEE Spectrum includes an article, “Of Mice and Menus,” on graphical user interfaces past and present. The authors of that article consulted several people who contributed to or are mentioned in this Star retorspective.

In the following bibliograhy, readings are categorized according to wheter they pertain to wrok done prior to the establishment of Xerox PARC, to work done at PARC, to the original Star design done at Xerox SDD,8 to enhancements to Star and ViewPoint, and to work on related topics.

Pre-Xerox

Bush, V., “As We May Think,” Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 176, No. 1, July 1945, pp. 101-108.

Engelbart, D.C. and W.K. English, “A Research Center for Augmenting Human Intelect,” Proc. FJCC, Vol. 33, AFIPS, 1968, pp. 395-410.

English, W.K., D.C. Engelbart, and M.L. Berman, “Display-Selection Techniques for Text Manipulation,” IEEE Trans. Human Factors in Electronic, HFE-8, 1967, pp. 21-31.

Kay, A.C. The Reactive Engine, PhD thesis, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, 1969.

Sutherland, I.E., Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communications System, PhD thesis, M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., 1963.

Xerox pre-Star

Card, S., W.K. English, and B. Burr, “Evaluation of Mouse, Rate-Controlled Isometric Joystick, Step Keys, and Text Keys for Text Selection on a CRT,” Ergonomics, Vol. 21, 1978, pp. 601-613.

Ellis, C, and G. Nutt, “Computer Science and Office Information Systems,” Xerox PARC Tech. Report SSL-79-6, 1979.

Geschke, C.M., J.H. Morris, Jr., and E.H. Satter-thwaite, “Early Experience with Mesa,” Comm. ACM, Vol. 20, No. 8, 1977, pp. 540-553.

Ingalls, D.H., “The Smalltalk Graphics Kernel,” Byte, Vol. 6, No. 8, Aug. 1981, pp. 168-194.

Kay, A.C., and A. Goldberg, “Personal Dynamic Media,” Computer, Vol. 10, No. 3, March 1977, pp. 31-41.

Kay, A.C., Microelectronics and the Personal Computer, Scientific American, Vol. 237, No. 3, Sept. 1977, pp. 230-244.

Smith, D.C, Pygmalion: A Computer Program to Model and Simulate Creative Thought, Birkhauser Verlag, Basel and Stuttgart, 1977.

Thacker, C.P., et al., “Alto: A Personal Computer,” in Computer Structures: Principles and Examples, D. Siewioek, C.G. Bell, and A. Newell, eds., McGraw Hill, New York, 1982.

Star

Curry, G., et al., “Traits – An Approach to Multiple-Inheritance Subclassing,” Proc. ACM Conf. on Office Automation Systems (SIGOA), 1982.

Dalai, Y.K., “Use of Multiple Networks in the Xerox Network System,” Computer, Vol. 15, No. 10, Oct. 1982, pp. 82-92.

Johnsson, R.K., and J.D. Wick, “An Overview of the Mesa Processor Architecture,” SIGPlan Notices, Vol. 17, No. 4, 1982.

Lipkie, D.E., et al., “Star Graphics: An Object-Oriented Implementation,” Computer Graphics, Vol. 16, No. 3, July 1982, pp. 115-124.

Shoch, J.F., et al., “Evolution of the Ethernet Local Computer Network,” Computer, Vol. 15, No. 9, Aug. 1982, pp. 10-27.

Smith, D.C, et al., Designing the Star User Interface, Byte, Vol. 7, No. 4, April 1982, pp. 242-282.

Sweet, R.E., and J.G. Sandman, Jr., “Empirical Analysis of the Mesa Instruction Set,” SIGPlan Notices, Vol. 17, No. 4, 1982.

Star/ViewPoint enhancements

Becker, J., “Typing Chinese, Japanese, and Korean,” Computer, Vol. 18, No. 1, Jan. 1985, pp. 27-34.

Becker, J., “Arabic Word Processing,” Comm. ACM, Vol. 30, No. 7, July 1987, pp. 600-610.

Bewley, W.L., et al., Human Factors Testing in the Design of Xerox’s 8010 Star Office Workstation, Proc. ACM Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1983, pp. 72-77.

Bushan, A., and M. Plass, “The Interpress Page and Document Description Language,” Computer, Vol. 19, No. 6, June 1986, pp. 72-77.

Curry, G., and R. Ayers, “Experience with Traits in Star,” Programming Productivity: Issues for the Eighties, IEEE Computer Society Press, Los Alamitos, Calif., 1986, Order #681.

Halbert, D., “Programming by Example,” Xerox OSD Tech. Report OSD-T84-02, 1984.

Lewis, B., and J. Hodges, “Shared Books: Collaborative Publication Management for an Office Information System,” Proc. ACM Conf. on Office Information Systems, 1988.

Miscellaneous

Bly, S., and J. Rosenberg, “A Comparison of Tiled and Overlapping Windows,” Proc. ACM Conf. on Computer-Human Interaction, 1986, pp. 101-106.

Goldberg, A., Smalltalk-80: The Interactive Programming Environment, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading, Mass., 1984.

Goldberg, A., and D. Robson, Smalltalk-80: The Language and its Implementation, Addison-Wesley Publishing, Reading, Mass., 1984.

Halasz, F., and T. Moran, “Analogy Considered Harmful,” Proc. ACM Conf. on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Gaithersburg, MD, 1982, pp. 383-386.

Houston, T., “The Allegory of Software: Beyond, Behind, and Beneath the Electronic Desk,” Byte, Dec. 1983, pp. 210-214.

Johnson, J., “Calculator Functions on Bitmapped Computers,” SIGCHI Bulletin, Vol. 17, No. 1, July 1985, pp. 23-28.

Johnson, J., “How Closely Should the Electronic Desktop Simulate the Real One?” SIGCHI Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 2, Oct. 1987, pp. 21-25.

Johnson, J., “Modes in Non-Computer Devices,” in press, Int’l J. Man-Machine Studies, 1989.

Johnson, J., and R. Beach, “Styles in Document Editing Systems,” Computer, Vol. 21, No. 1, Jan. 1988, pp. 32-43.

Malone, T.W., “How Do People Organize Their Desks: Implications for the Design of Office Information Systems,” ACM Trans. on Office Information Systems, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1983, pp. 99-112.

Rosenberg, J.K., and T.P. Moran, “Generic Commands,” Proc. First Int’l Conf. on Human-Computer Interaction (Interact-84), 1984, pp. 1,360-1,364.

Teitelman, W., “A Tour Through Cedar,” IEEE Software, April 1984.

Whiteside, J., et al., “User Performance with Command, Menu, and Iconic Interfaces,” Proc. ACM SIGCHI ’85, 1985, pp. 185-191.